Hey all!

I thought I’d take a look at something different today. I’d like to examine the overall design of the World of Greyhawk Fantasy Setting, as designed by Gary Gygax, and what it tells us about campaign design in general.

Fortunately, Gygax et al have given us insights into the process over the years in various online fora. For example, Rob Kuntz (eventual co-DM of the campaign) tells us:

“Understanding Greyhawk Geography (via a Designer’s Commentary) 101″

This is the scoop!

Greyhawk Castle and City were developed at the same time.

Nearby outdoor adventures were added (the Dark Druids by myself, Circle of Eight stuff by Gary, etc., etc.) though this was much later (2nd Castle period).

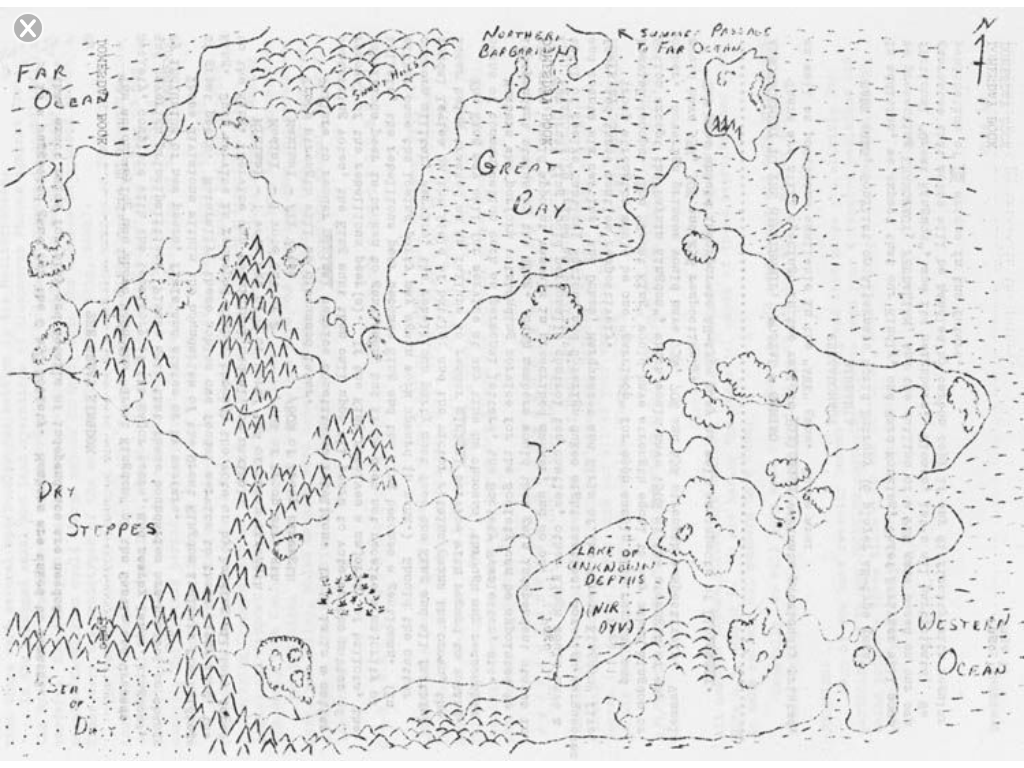

The map for the WoG Outdoor was a color pencil 8 1/2 x 11” drawn by EGG, which highlighted the Flanaess (most of what Darlene then redrew with Gary’s direction for the Folio release of WoG). Blackmoor was situated to the extreme NW (as how Arneson, in Minneapolis/St. Paul, was in geographical relation to Lake Geneva).

When WoG was released, the modules were then situated in it. As we know, there was some back filling involved with some of these as EGG wanted a place where all of his designs, as well as those of others writing for the milieu, could be accessed geographically. The same holds true for Dragon articles from these time periods. Anything GH was being linked with the outdoor.

There were plans for WoG regional areas, with the first one “The Wild Coast” as sketched by myself, and of course EGG had nearly finished Stoink around that time, and of course I was planning on what to link the eight-pointed star from WG5, etc., etc.

But, for the most part, excepting for modules, the outdoor remained skeletal. (Q&A thread on Pied Piper Publishing forums)

That’s consistent with the known history of the setting, which began with this map as part of the Castles & Crusades Society game:

The earliest version of the setting was set on a planet…

“…much like our earth. Think of the world of Aerth as was presented for the MYTHUS FRPG. The city of Greyhawk was located on the lakes in about the position that Chicago is, and Dyvers was north ar the Milwaukee location. The general culture was pseudo medieval European. Some of the kingdoms shown on the WoG map were around the adventure-central area, the City of Greyhawk.” (EGG Q&A ENWorld thread)

However, once the decision was made to publish the setting commercially, the original campaign map was altered to accommodate the large map size that was available:

I found out the maximum map size TSR could produce, got the go-ahead for two maps of that size, then sat down for a couple of weeks and hand-drew the whole thing. After the maps were done and the features shown were named, I wrote up brief information of the features and states. Much of the information was drawn from my own personal world, but altered to fit the new one depicted on the maps. (EGG Q&A ENWorld Thread)

It is this version of the setting, with the Darlene maps which most of us are most familiar with, which I want to explore in some detail. After the publication of the Folio, which contained thumbnail sketches of the various states and wilderness features, came almost immediately the Gold Box set, which expanded the setting significantly with its own deities, encounter tables, weather, etc. But looking at the setting itself is highly instructive as well. Let’s try to boil things down into a few easy-to-list design principles.

For instance, the theme of the fallen civilization after a catastrophe looms large. Analogous to how the fall of the Roman Empire was viewed in medieval Europe, the mutual destruction of the Baklunish Empire and the Suel Imperium was foundational in the make-up of the Flanaess in 576 CY. Their war triggered the migration of the Oeridian peoples who went on to found the continent-spanning Great Kingdom of Aerdy, a longing to restore lost glory is the motivation for the shadowy Scarlet Brotherhood, and the antagonism between the Baklunish and the Suel/Oeridians continues to the present day. While it is never said outright, the existence of high-technology artifacts like the Machine of Lum the Mad and the Mighty Servant of Leuk-o hint at a much higher level of civilization in ancient times.

Design Principle One: Fallen Civilization as background and impetus for the modern world

To say that Greyhawk has many resemblances to Europe is well-known. The Great Kingdom of Aerdy is its Holy Roman Empire, once spanning the whole of the Flanaess and invincible, now in strategic retreat and engulfed by ineffectual and evil government. Its outlying territories rebelled long ago, those of which are on its borders are active enemies, and even its central provinces have questionable loyalty to the Malachite Throne. Add to this pressure from barbarians and humanoids in the north, and we get the sense of impending large-scale war, both civil and regular, over an enormous portion of the continent. (This theme was, of course, carried through to the utter dissolution of the Great Kingdom in the later From the Ashes boxed set, but I’m trying to confine my analysis to the Folio/Gold Box era.)

Design Principle Two: Politics and history create dynamic possibilities in the setting

Other parallels to medieval Europe exist, but the principle . Perrenland, with its mercenary pike units, is Switzerland. The Ice, Frost, and Snow barbarians are Viking-era Norway, Denmark, and Sweden respectively. However, beyond those concrete examples, we have a mix of generic feudal European states from different eras. Keoland, Furyondy, and Nyrond are all cut from the same cloth, and it’s not really possible to differentiate them along historical European lines (i.e., there’s no easily identifiable France, or Hungary). Others, such as the Yeomanry or the Sea Princes, have no real historical analogues. And, naturally, the demi-human and humanoid states (Ulek, Iuz, Bone March, etc.) have no real-world counterparts. So there’s enough historical material to make the setting accessible, but not so much as to make it hidebound.

Design Principle Three: Make the setting familiar, with a few close parallels, but don’t slavishly copy history

One of the things that set the original Folio and Gold Box apart was their almost Hemingway-esque brevity. Each description of the various realms was a couple of paragraphs at most, but they were brimming with potential, hints, and insinuations rather than spelling out relationships and details. It was this policy of hinting rather than telling that maximized the ability of each Dungeon Master to make the setting their own. The original Folio might have taken the principle slightly too far (with no mention of gods), but the Gold Box still retained the general mantra of “less is more.”

Design Principle Four: Don’t feel like you need to describe everything in detail; leave enough hints for the DM to take the baton and run with it

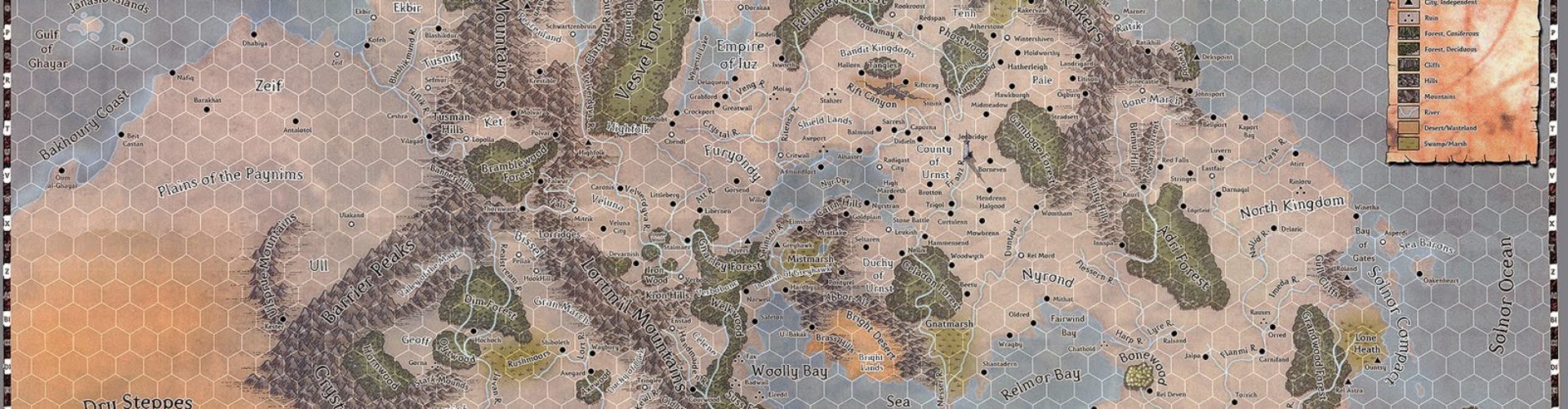

Let’s take a moment to look at the map itself:

Notice anything about the layout of the mountains, forests, and other terrain features? There’s a very busy section right in the middle of the map, while things get progressively less “interesting” geography-wise as you get further out from the center. That center, of course, is where Gygax’s original campaign was set, where the City of Greyhawk and Temple of Elemental Evil are, where the ruins of Castle Greyhawk and Maure Castle are, and so forth. Here it is in more detail:

Notice the lovely and interesting geography immediately surrounding the centerpiece of the campaign; the City of Greyhawk. You have lake, ocean, hills, plains, mountains, hills, desert, and forests all within 10 hexes of the city. There are five nation-states, two anarchic regions (the Wild Coast and Bandit Kingdoms), plus wilderness including the mysterious Rift Canyon, all convenient to the city where adventurers start their careers. The plan was to detail the city and the iconic dungeons beneath Castle Greyhawk, but we all know what happened to that. There’s nowhere else remotely like this in the setting, with so much diversity of terrain in so small an area, especially adjacent to a Mecca for adventurers. You could literally have an entire campaign just on the piece of the map I clipped out above, and never need to go outside its boundaries. And yet all those other areas are there, in much less detail, waiting for the DM to flesh it out. This is where the “campaign tent-pole” would go.

Design Principle Five: Have an obvious region for adventure to make things easier on the DM (an “adventure-center”), while leaving the rest of the setting painted in broader strokes for DM development

To build on that last principle, it’s worth pointing out that Gygax had plans to do the same thing in at least three other sections of the World of Greyhawk. Len Lakofka had the Spindrift Isles (later renamed the Lendore Isles), which were just starting to be developed as a sub-setting with the publication of L1 The Secret of Bone Hill and L2 Assassin’s Knot, plus his fleshing out of the Suel pantheon of deities for the setting as a whole. Frank Mentzer was to have Aquaria, a land to the east across the Solnor Ocean, which was the setting for the R1-4 series of modules, To the Aid of Falx, The Investigation of Hydell, The Egg of the Phoenix, and Doc’s Island. The last, François Marcela-Froideval’s “Empire of Lhynn” setting (itself the setting in that author’s series of graphic novels, Chroniques de la Lune Noire), would have been set in the far west of the continent of Oerik, but nothing was ever officially published, aside from the mention of a few place-names in the Oerik map printed in Dragon Annual #1. Such a strategy would allow for bringing in fresh ideas and taking things in directions that the original designer would never have done, but still within the overall scope and structure of the Greyhawk campaign and guided by the overall vision of the original creator. More than just taking some of the workload off of Gygax’s shoulders, doing so was a way to introduce new ideas and new blood into the campaign, much as Gygax did back in the early, pre-publication days by bringing Kuntz on as co-DM.

Design Principle Six: Consider farming out additional adventure-centers to other designers, within the framework of the campaign as a whole

It’s worth exploring how the setting was implemented beyond the campaign set itself; that is, the adventure modules that were produced, especially in the early days. As we saw in Rob Kuntz’s quote at the beginning of this article, the locations of some of the earliest adventures (G1-3, D1-3, S1, S2, and T1) were “backfilled” into existing locations in the setting as it was eventually published. But those modules weren’t developed in a vacuum, as they contain references to nations and locations that made their way into the published setting (T1 especially).

However, the brilliance of the early modules that came out after the publication of the Folio and Gold Box is that they weren’t just information dumps or sourcebooks. As I wrote about a few years ago, they managed to communicate new and interesting information about the setting by putting the player characters in the middle of some action that was tied to the setting itself. I called it “Showing, not Telling.” Essentially, it means that adventures are tied into the setting and can add new details, as long as those details are given in the context of the action of the adventure. When we first got the details about Zuggtmoy and the Temple of Elemental Evil itself, it was because they were necessary for the DM to give to the players in order to get the most out of the adventure. The same goes for the Slavers series (A1-4), the Saltmarsh series (U1-3), S4 The Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth, WG4 The Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun, and others. Contrast those modules with later efforts like Iuz the Evil or Marklands, which were plotless encyclopedias that imparted far too much information (in my humble opinion) in a far too unfriendly format.

Design Principle Seven: Use adventures to add depth and detail, but show, don’t tell

Finally, we come to one of the most contentious issues within Greyhawk fandom; advancing the timeline. After Gygax’s departure from TSR, the setting was famously taken forward 9 years into the future, from 576 CY to 585 CY, with the changes being explained in two boxed sets; Greyhawk Wars and From the Ashes. As one might tell from the title of the latter, much of the existing campaign setting was dramatically changed. Entire nations such as the Great Kingdom ceased to be, the Scarlet Brotherhood came out of the shadows as an evil empire of its own, Iuz became the major bad guy of the setting by conquering a huge swath of the North, major NPCs were killed (Tenser, Otiluke) or had their personalities completely rewritten (Robilar, Rary) to accommodate the changes, and a huge number of fans of the setting were enraged by the change to their beloved setting.

I’m not going to get into the pros and cons of the specific changes here, but I will point out that the general concept of “advancing the timeline” was far from something alien to the Greyhawk setting before the publication of Greyhawk Wars and From the Ashes. Indeed, Gygax himself advanced the timeline in a series of articles in Dragon magazine called Greyhawk’s World. Where the original Folio and Gold Box were set in 576 CY, the articles carried the setting forward through 577 and into 578, detailing troop movements and battles, major political events, and the like. It was much more akin to the sort of updates one would see in a miniatures wargame campaign, and I think it speaks to Gygax’s mindset that he still thought in those terms. I should also point out that the series was never completed, and I took it upon myself to do so, completely unofficially, of course. By advancing the timeline and showing these sorts of large-scale events, happening almost in real time as it were, the setting took on a life that merely presenting a history couldn’t do. I don’t think those articles would work nearly as well as a sort of annual update to the boxed set. The fact that they were released in dribs and drabs helped add to the sense that Greyhawk was a dynamic setting. It’s also worth pointing out that those officially-published updates never covered the central Flanaess, that “adventure-center” I identified above. Dancing around the center like that helped reduce the issue of official updates contradicting events in a particular home campaign, as they were largely kept to the periphery, and didn’t involve any radical transformations.

Design Principle Eight: Advancing the timeline is okay, as long as it adds details like an adventure module, rather than changes details that might contradict local campaigns

As to what would have become of the setting if Gygax had been allowed to continue its development, we have three juicy tidbits.

Speculation…

Timelines would be loose indeed

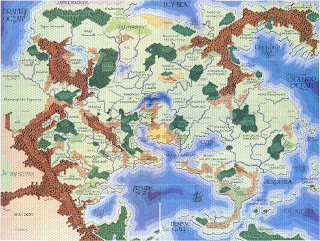

The would be a complete globe with more continents and states thereon with contributions from Len Lakofka and Francois Marcela-Froideval/

There would be several WoG sourcebooks detailing places such as the Great Kingdom, the “Barbarians (Frost, ice, Snow),” etc.

A major module would be done regarding the area around the Rift and the place proper. Another dealing with the Sea of Dust would be done. Possibly adventures regarding the Scarlet Brotherhood and the Horned Society would be available. Likely a couple of more from Len and Francois would be in the line.

There would be some “portal accessed” adventures, these likely found in a series of modules detailing more of the Underdark and the Sunless Sea. The portals would lead to non-fantasy-genre settings.

In all, for every question answered regarding the world, at least one new one would be created and left unanswered, for my purpose was to have a world that the DM could complete and customize as suited his group. (EGG Q&A thread on ENWorld)

It’s worth noting that here Gygax contradicts my own advice and states he was planning on releasing sourcebooks of the Great Kingdom and the barbarian realms in the northeast. However, given his track record of such products after his departure from TSR, particularly at the time he wrote that (2003), he speaks in that same thread of “playtesting” sourcebooks. So I believe his idea of a sourcebook would be much more adventure-oriented than what we got with Marklands, etc.

And there’s this bit about other continents in Oerth as well:

Likely two large continents would have been added. The nearest would house cultures akin to the Indian, Burmese, Indonesian, Chinese, Tibetan, and Japanese. Another would likely have been the location of African-type cultures, including the Egyptian. A Lemurian culture would have been based off the Central and South American cultures of the Aztec-Mayay-Inca sort. (Ibid)

And finally, the quote that got me started on my recent series expanding out the Baklunish pantheon:

I had planned a different pantheon for the Baklunish, but I never got around to detailing it. Should the majority be satisfied with the deities as presented, then indeed I would agree that Heironeous is a logical choice for the chief deity of the Caliphate of Ekbir.

The reason I wished to include another pantheon is, of course, obvious, for lacking even the common ground of a shared pantheon, the friction would be greater between these peoples and the east. (Oerth Journal #12, p. 5)

So to recap, here are the lessons I come away with, from an examination of the original World of Greyhawk as published in the Folio and Gold Box. I certainly will find them useful when creating my next home-grown campaign, and having them crystallized into these bullets will also help me keep my Greyhawk campaign play focused as well.

- Design Principle One: Fallen Civilization as background and impetus for the modern world

- Design Principle Two: Politics and history create dynamic possibilities in the setting

- Design Principle Three: Make the setting familiar, with a few close parallels, but don’t slavishly copy history

- Design Principle Four: Don’t feel like you need to describe everything in detail; leave enough hints for the DM to take the baton and run with it

- Design Principle Five: Have an obvious region for adventure to make things easier on the DM (an “adventure-center”), while leaving the rest of the setting painted in broader strokes for DM development

- Design Principle Six: Consider farming out additional adventure-centers to other designers, within the framework of the campaign as a whole

- Design Principle Seven: Use adventures to add depth and detail, but show, don’t tell

- Design Principle Eight: Advancing the timeline is okay, as long as it adds details like an adventure module, rather than changes details that might contradict local campaigns

A great examination of the original concept of the open sandbox. It has the wheels spinning for sure. This gives me an idea for a project, whereby using these rules a community could build a sandbox world hex by hex.

An established set of directives guide the creative hand. Large areas like cities would be divided up, to give sections flavor loosely, again leaving plenty of room for DM interjection of “Their gritty rogues’ bar, Their conniving fence jewelry shop etc, etc.

So you would have your seedy area down by the docks, Alleys attached to the central bazaar, with a general feel and a few standout NPC’s for flavor but nothing so overpowering it forces a DM’s hand.

By this examination, these areas were all built by different minds to make the Greyhawk we all lovingly remember. Very good piece and I think your eight design principles are spot on!

An excellent piece as usual, Mr. Bloch. What I find really interesting is to compare these principles and see how they apply to Greyhawk and TSR/WOTC’s other most significant settings, Dragonlance and Forgotten Realms.

1. Greyhawk obviously has the Twin Cataclysms. Forgotten Realms and Dragonlance have this too, with the civilization of Netheril and the Kingpriest’s Cataclysm, respectively.

2. Greyhawk has this with the Great Kingdom of Aerdy, the Suel barbarians and Perrenland, as Mr. Bloch pointed out. It also has the Flan paralleling the North American First Nations (Cree, Sioux, Navajo, etc.) and the Olman standing in for the South American First Nations (Maya, Olmec, Mapuche, etc.)

Dragonlance has its own First Nations equivalents (the Plainsfolk for North America and possibly the Nordmaarians for South America), and probably Solamnia as a stand-in for medieval England or France with their formal orders of chivalric knighthood. Forgotten Realms has Mulhorand as an equivalent to ancient Egypt, Unther to Mesopotamia, Durpar and its allies for India, and even the Shou Lung for China.

3. Again, Greyhawk, Dragonlance and Forgotten Realms all pretty much take the same approach. Dragonlance places like Neraka, Silvanesti, Tarsis, and Istar don’t really have real-world equivalents, and neither do Realms places like the Dalelands, Zhentil Keep or Waterdeep.

4. This is where we first start seeing major divergences between Greyhawk and the other settings that would follow it. Dragonlance and Forgotten Realms both have scads of novels for almost every significant historical or setting event, in addition to assorted modules and sourcebooks for different regions, professions, etc. The only difference is that Dragonlance’s materials are often a lot more contradictory.

Greyhawk’s novels aren’t really canon (thankfully) while its sourcebooks were much fewer and farther between. While the Dragonlance and Forgotten Realms novels are often decried, especially by grognards, I also wonder how many people were actually introduced to D&D and the gaming hobby by those novels-and how much that helped maintain the hobby up until today.

5. Here Greyhawk returns to common ground with Dragonlance and Forgotten Realms. The City of Greyhawk and its environs are Greyhawk’s representative of this principle, Abanasinia and Solamnia are Dragonlance’s contribution, and Waterdeep and the Dalelands are the Realms’ example, as judged by how much focus they often get in source materials.

6. Greyhawk didn’t really get the chance to do this, and the original Dragonlance campaign had everyone from Jeff Grubb to Harold Johnson to Douglas Niles contributing material along with Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman. As for Forgotten Realms, I seem to recall R.A. Salvatore talking about how Faerun was divided up between different authors with each of them getting “dibs” on a particular region. Salvatore’s own region was the northwest around the Spine of the World and Silverymoon.

So all three settings used this principle in the same way, even if Greyhawk’s use of it was truncated.

7. Along with Greyhawk, Dragonlance also did this with the original 14-module Chronicles series, which systematically gave players and DMs information about different places as the story took them there. It was an innovative way to do it, especially with the addition of poems and music, even if it wasn’t always as successful as envisioned. That said, the Weis and Hickman novels largely supplanted the modules in terms of detailing the setting.

The Realms is the real standout here, making changes through novels rather than modules (and when they did produce modules, such as with the Avatar Crisis, those modules were so railroading they made the Dragonlance Chronicles look like an open sandbox). Admittedly, WOTC may have changed this, since I recall some of Salvatore’s Drizzt novels referring to the Rise of Tiamat module.

8. Along with principle #4, this is the big divergence between Greyhawk and the other settings. Dragonlance was by far the biggest offender with events like the War of Souls and the Chaos War, but Forgotten Realms did it too with the Time of Troubles and the Spellplague. That said, the Realms also reversed some of their drastic fiat changes (e.g. reviving dead gods like Bane) in a less dramatic way-and it’s probably not an accident that these changes were as I understand it better received by Realms fans.

In fairness, Greyhawk did this too with From The Ashes and The Adventure Begins, as Gary Holian and company tried to clean up the mess Carl Sargent had to deal with. One of my favorite elements of the Living Greyhawk Gazetteer was how much information the authors added about everything from coinage to history that didn’t otherwise muck with local campaigns. And Living Greyhawk was another great way to advance the timeline-while the Triads had editorial control, it was less of an issue because the Living Greyhawk players themselves directly influenced the stories’ outcomes.

Good stuff

Same here, great stuff indeed. I don’t have anything to contribute but I very much appreciate this deep analysis by Mr. Bloch and CruelSummerLord. Thanks!

Terrific thoughts, Joe, very thought-provoking! I see a lot of the same things in our creative work for Greyhawk Reborn, though reading this also opens up my mind to some other ideas. I will be sharing this with our Greyhawk Reborn players and especially our admins. Thank you so much for Greyhawk for this work, and all the work you do

Very interesting indeed! I had great interest in Frank’s aborted attempt to detail Empyrea to the east, and I would love to see other “fan-based” and “for publication” efforts to expand this material using these design principles.